阅读娜奥米·诺维克的下一部小说《旋转银器》的节选

在过去的十年里,奇幻小说作家娜奥米·诺维克(Naomi Novik)凭借她的《拿破仑时代场景特梅莱尔》(Alternative Napoleonic era set Temeraire)系列赢得了声誉,在该系列中,士兵们在龙的头顶上飞翔,投入战斗。但在2015年,她改变了方向,写了一部受经典童话启发的小说《连根拔起》。这一努力为她赢得了2016年的星云奖最佳小说奖和轨迹奖最佳幻想小说奖。她的下一部小说《旋转的银色》将她带回了童话的根源。

这本书将于2018年7月上市,我们有一个摘录和封面供您查看。诺维克在一封电子邮件中告诉《边缘》杂志,她的新小说出自最近的一本选集《星光森林:新童话》。她选择了朗普斯汀作为她的故事的灵感来源,“当我开始写我想写的短篇小说时,它从我身边跑开了。”她完成了选集的短篇小说,但继续写作。从那时起,它发展成为小说。

近年来,重新构思的童话故事开始流行,从凯瑟琳·阿登(Katherine Arden)的俄罗斯民间故事启发的****《熊与夜莺》和《塔里的女孩》,到米根·斯普纳(Meagan Spooner)的《美女与野兽》启发的《狩猎》。诺维克说,对她来说,最好的故事是在亲密的公司之间一遍又一遍地讲述的故事。童话是实现这一目标的理想之选,因为它们为听众所熟悉,而且不受版权法的约束。”“你不能说,我想告诉你一个关于哈利波特的不同故事,”她说,“相反,你必须在你和你试图交谈的故事之间建立法律上的距离,当你做到这一点时,你也创造了情感上的距离。”因为童话故事在公共领域,它们可以被无休止地重新混合和想象,并保持这种情感联系。

诺维克解释说,在这本书中,被连根拔起的人扮演了一个重要角色,尽管他们不是共同宇宙的一部分。”直到我写《旋转银币》的时候比较晚,我才真正意识到,《被连根拔起》在很大程度上是关于我母亲的经历和她在我家庭中的地位,而《旋转银币》的大部分都是在处理我父亲的故事——在他们来到美国之前逃到俄罗斯并生活在****政权下的立陶宛犹太人。

这是纺银和它的封面的第一章。

The real story isn’t half as pretty as the one you’ve heard. The real story is, the miller’s daughter with her long golden hair wants to catch a lord, a prince, a rich man’s son, so she goes to the moneylender and borrows for a ring and a necklace and decks herself out for the festival. And she’s beautiful enough, so the lord, the prince, the rich man’s son notices her, and dances with her, and tumbles her in a quiet hayloft when the dancing is over, and afterwards he goes home and marries the rich woman his family has picked out for him. Then the miller’s despoiled daughter tells everyone that the moneylender’s in league with the devil, and the village runs him out or maybe even stones him, so at least she gets to keep the jewels for a dowry, and the black**ith marries her before that firstborn child comes along a little early.

Because that’s what the story’s really about: getting out of paying your debts. That’s not how they tell it, but I knew. My father was a moneylender, you see.

He wasn’t very good at it. If someone didn’t pay him back on time, he never so much as mentioned it to them. Only if our cupboards were really bare, or our shoes were falling off our feet, and my mother spoke quietly with him after I was in bed, then he’d go, unhappy, and knock on a few doors, and make it sound like an apology when he asked for some of what they owed. And if there was money in the house and someone asked to borrow, he hated to say no, even if we didn’t really have enough ourselves. So all his money, most of which had been my mother’s money, her dowry, stayed in other people’s houses. And everyone else liked it that way, even though they knew they ought to be ashamed of themselves, so they told the story often, even or especially when I could hear it.

My mother’s father was a moneylender, too, but he was a very good one. He lived in Vysnia, forty miles away by the pitted old trading road that dragged from village to village like a string full of **all dirty knots. Mama often took me on visits, when she could afford a few pennies to pay someone to let us ride along at the back of a peddler’s cart or a sledge, five or six changes along the way. Sometimes we caught glimpses of the other road through the trees, the one that belonged to the Staryk, gleaming like the top of the river in winter when the snow had blown clear. “Don’t look, Miryem,” my mother would tell me, but I always kept watching it out of the corner of my eyes, hoping to keep it near, because whoever was driving the cart would slap the horses and hurry them up until it vanished again.

One time, we heard the hooves behind us as they came off their road, a sound like ice cracking, and the driver beat the horses quick to get the cart behind a tree, and we all huddled there in the well of the wagon among the sacks, my mother’s arm wrapped around my head holding it down so I couldn’t be tempted to take a look. They rode past us and did not stop. It was a poor peddler’s cart, covered in dull tin pots, and Staryk knights only ever came riding for gold. The hooves went jangling past, and a knife-wind blew over us, so when I sat up the end of my thin braid was frosted white, and all of my mother’s sleeve where it wrapped around me, and our backs. But the frost faded, and as soon as it was gone, the peddler said to my mother, “Well, that’s enough of a rest, isn’t it,” as if he didn’t remember why we had stopped.

“Yes,” my mother said, nodding, as if she didn’t remember either, and he got back up onto the driver’s seat and clucked to the horses and set us going again. I was young enough to remember it afterwards a little, and not old enough to care about the Staryk as much as about the ordinary cold biting through my clothes, and my pinched stomach. I didn’t want to say anything that might make the cart stop again, impatient to get to the city and my grandfather’s house.

My grandmother would always have a new dress for me, plain and dull brown but warm and well-made, and each winter a pair of new leather shoes that didn’t pinch my feet, and weren’t patched and cracked around the edges. She would feed me to bursting three times every day, and the last night before we left she would always make cheesecake, her cheesecake, which was baked golden on the outside and thick and white and crumbly inside and tasted just a little bit of apples, and she would make decorati*** with sweet golden raisins on the top. After I had slowly and lingeringly eaten every last bite of a slice wider than the palm of my hand, they would put me to bed upstairs, in the big cozy bedroom where my mother and her sisters had used to sleep as girls, in the same narrow wooden bed carved with doves. My mother would sit next to her mother by the fireplace, and put her head on her shoulder. They wouldn’t speak, but when I was a little older and didn’t fall asleep right away, I would see in the firelight glow that both of them had a little wet track of tears down their faces.

We could have stayed. There was room in my grandfather’s house, and welcome for us. But we always went home, because we loved my father. He was terrible with money, but he was endlessly warm and gentle, and he tried to make up for his failings: he spent nearly all of every day out in the cold woods hunting for food and firewood, and when he was indoors there was nothing he wouldn’t do to help my mother. No talk of woman’s work in my house, and when we did go hungry, he went hungriest, and snuck food from his plate to ours. When he sat by the fire in the evenings, his hands were always working, whittling some new little toy for me or something for my mother, a decoration on a chair or a wooden spoon.

But winter was always long and bitter, and every year I was old enough to remember was worse than the one before. Our town was unwalled and half-nameless; some people said it was called Pakel, for being near the road, and those who didn’t like that, because it reminded them of being near the Staryk road, would shout them down and say it was called Pavys, for being near the river, but no one bothered to put it on a map, so no decision was ever made. When we spoke, we all only called ittown. It was welcome to travelers, near the halfway mark between Vysnia and Minask, and a **allish river crossed the road running from east to west. Many farmers brought their goods by boat, so our market day was busy. But that was the limit of our importance. No lord concerned himself very much with us, and the tsar in Mokva not at all. I could not have told you who the tax collector worked for until one visit to my grandfather’s house I learned accidentally that the Duke of Vysnia was angry because the receipts from our town had been creeping steadily down year to year. The cold kept stealing out of the woods earlier and earlier, eating at our crops.

And the year I turned sixteen, the Staryk came too, during what should have been the last week of autumn, before the late barley was all the way in. They had always come raiding for gold, once in a while; people told stories of half-remembered glimpses, and the dead they left behind. But they had grown more rapacious as the winters grew worse. There were still a few leaves clinging to the trees when they rode off their road and onto ours, and they went only ten miles past our village to the rich monastery down the road, and there they killed a dozen of the monks and stole the golden candlesticks, and the golden cup, and all the ic*** painted in gilt, and carried away that golden treasure to whatever kingdom lay at the end of their own road.

The ground froze solid that night with their passing, and every day after that a sharp steady wind blew out of the forest carrying whirls of stinging snow. Our own little house stood far apart from the rest of town, without other walls nearby to share in breaking the wind, and we grew ever more thin and hungry and shivering. My father kept making his excuses, avoiding the work he couldn’t bear to do. But even when my mother finally pressed him and he tried, he only came back with a scant handful of coins, and said in apology for them, “It’s a bad winter. A hard winter for everyone,” when I didn’t believe they’d even bothered to make him that much of an excuse. I walked through town the next day to take our loaf to the baker, and I heard women who owed us money talking of the feasts they planned to cook, the treats they would buy in the market. It was coming on midwinter. They all wanted to have something good on the table; something special for the festival, their festival.

So they had sent my father away empty-handed, and their lights shone out on the snow and the **ell of roasting meat slipped out of the cracks while I walked slowly back to the baker, to give him a worn penny in return for a coarse half-burned loaf that hadn’t been the loaf I’d made at all. He’d given a good loaf to one of his other customers, and kept a ruined one for us. At home my mother was making thin cabbage soup and scrounging together used cooking oil to light the lamp for the third night of our own celebration, coughing as she worked: another deep chill had rolled in from the woods, and it crept through every crack and eave of our run-down little house. We only had the flames lit for a few minutes before a gust of it came in and blew them out, and my father said, “Well, perhaps that means it’s time for bed,” instead of relighting them, because we were almost out of oil.

By the eighth day, my mother was too tired from coughing to get out of bed at all. “She’ll be all right soon,” my father said, avoiding my eyes. “This cold will break soon. It’s been so long already.” He was whittling candles out of wood, little narrow sticks to burn, because we’d used the last drops of oil the night before. There wasn’t going to be any miracle of light in our house.

He went out to scrounge under the snow for some more firewood. Our box was getting low too. “Miryem,” my mother said, hoarsely, after he left. I took her a cup of weak tea with a scraping of honey, all I had to comfort her. She sipped a little and lay back on the pillows and said, “When the winter breaks, I want you to go to my father’s house. He’ll take you to my father’s house.”

The last time we had visited my grandfather, one night my mother’s sisters had come to dinner with their hu**ands and their children. They all wore dresses made of thick wool, and they left fur cloaks in the entryway, and had gold rings on their hands, and gold bracelets. They laughed and sang and the whole room was warm, though it had been deep in winter, and we ate fresh bread and roasted chicken and hot golden soup full of flavor and salt, steam rising into my face. When my mother spoke, I inhaled all the warmth of that memory with her words, and longed for it with my cold hands curled into painful knots. I thought of going there to stay, a beggar girl, leaving my father alone and my mother’s gold forever in our neighbors’ houses.

I pressed my lips together hard, and then I kissed her forehead and told her to rest, and after she fell fitfully asleep, I went to the box next to the fireplace where my father kept his big ledger-book. I took it out and I took his worn pen out of its holder, and I mixed ink out of the ashes in the fireplace and I made a list. A moneylender’s daughter, even a bad moneylender, learns her numbers. I wrote and figured and wrote and figured, interest and time broken up by all the little haphazard scattered payments. My father had every one carefully written down, as scrupulous with all of them as no one else ever was with him. And when I had my list finished, I took all the knitting out of my bag, put my shawl on, and went out into the cold morning.

I went to every house that owed us, and I banged on their doors. It was early, very early, still dark, because my mother’s coughing had woken us in the night. Everyone was still at home. So the men opened the doors and stared at me in surprise, and I looked them in their faces and said, cold and hard, “I’ve come to settle your account.”

纺纱银于2018年7月10日上市。

- 发表于 2021-08-21 22:02

- 阅读 ( 85 )

- 分类:互联网

你可能感兴趣的文章

新预告片:坏头发,醒来,魔鬼所有的时间,等等

...天 HBO即将推出一部令人毛骨悚然的迷你剧,由裘德·洛和娜奥米·哈里斯主演,作为一个神秘岛屿的游客。作为一个迷路的粉丝,我有义务为任何关于神秘岛屿的系列发布预告片。该剧将于9月14日首播。 被**救了 《孔雀》将《...

- 发布于 2021-04-18 06:32

- 阅读 ( 163 )

狮门想要拍“五,六,七”动力游骑兵的电影

...斯饰演丽塔·厄普拉,以及达克雷·蒙哥马利、RJ·赛勒、娜奥米·斯科特、贝基·G和卢迪·林。两部《权力游侠》故事片已经上映:《强大的莫芬·权力游侠:电影》(1995)和《涡轮:权力游侠》(1997)。但是,嘿,一个老掉牙...

- 发布于 2021-05-05 04:30

- 阅读 ( 141 )

有史以来第一个龙奖入围名单旨在成为科幻迷的下一个主要奖项

...鬼魂行者,乔纳森·马贝里(Tor) 龙联盟,娜奥米·诺维克(德雷) **远去:热战,哈利斑鸠(德雷) 最佳世界末日小说 Ctrl-Alt反抗!,尼克·科尔(卡斯塔利亚之家) 追逐自由,玛丽娜·方丹(自行...

- 发布于 2021-05-07 01:17

- 阅读 ( 222 )

以下是2016雨果奖的获奖者

...个:尼尔·斯蒂芬森的小说(威廉·莫罗) 被娜奥米·诺维克(德雷饰)连根拔起 最佳中篇小说(17500-40000字短篇) Nnedi Okorafor的Binti(Tor.com) 丹尼尔·波兰斯基的《建设者》(Tor.com) 洛伊斯·麦克马...

- 发布于 2021-05-07 02:45

- 阅读 ( 272 )

首届龙奖突出了科幻小说和幻想小说的平民化一面

...(Roc) 最佳历史小说 龙联盟,娜奥米·诺维克(德雷) 德国,罗伯特·康罗伊(巴恩) 1635年:一群流氓,埃里克·弗林特和安德鲁·丹尼斯(贝恩) 1636年:基本美德,埃里克·弗林特和沃尔特·H。亨...

- 发布于 2021-05-07 11:32

- 阅读 ( 210 )

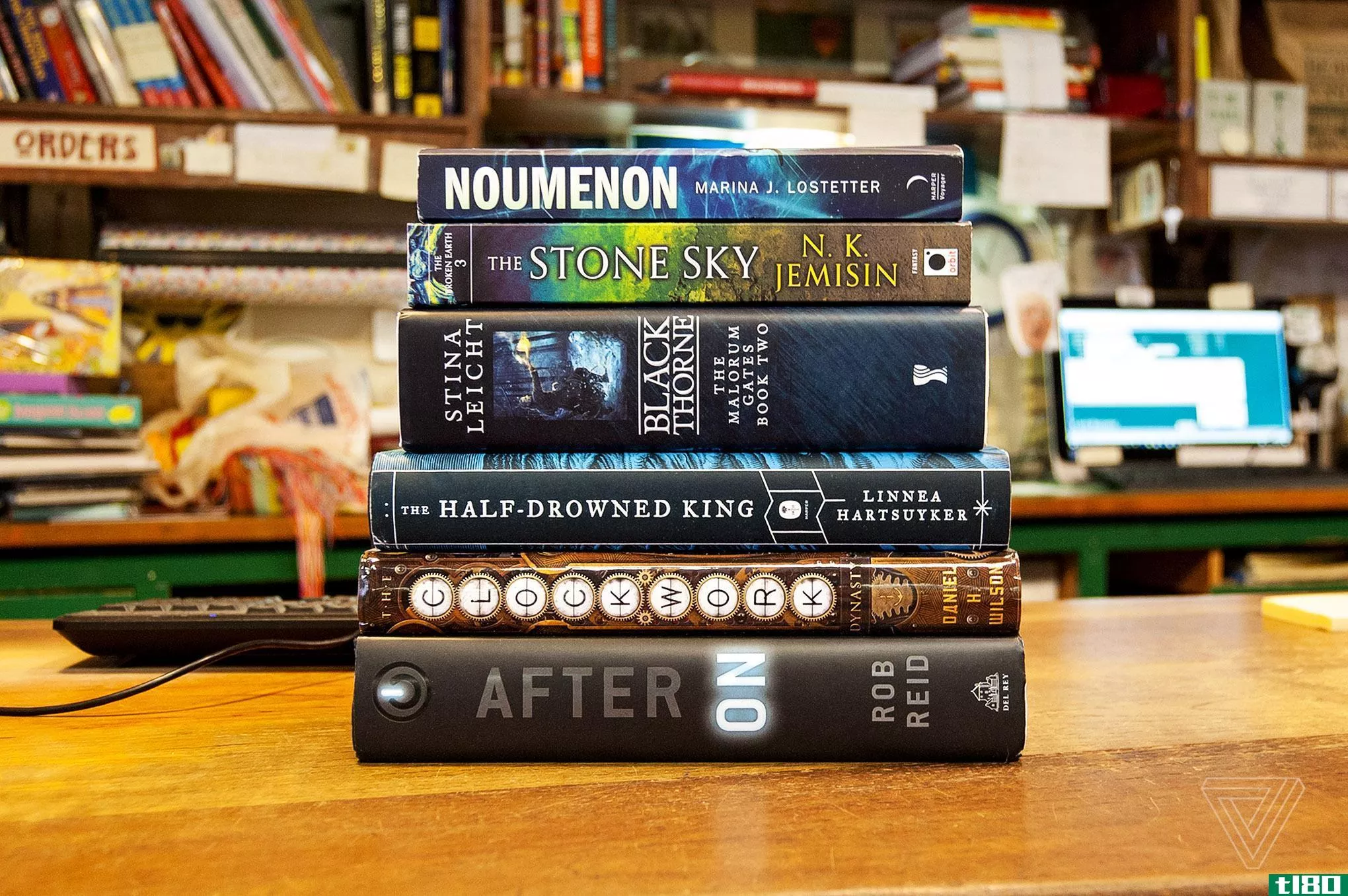

今年10月将有19本科幻小说和奇幻小说上架

...一些最优秀的作家汇集到一本书中。这本书包括纳奥米·诺维克、珍妮芙·瓦伦丁、查理·简·安德斯、卡琳·蒂德贝克、西奥多拉·戈斯、马克斯·格拉德斯通等著名作家的作品。 一切都属于未来,劳里·佩妮 在未来的牛津...

- 发布于 2021-05-08 01:21

- 阅读 ( 190 )

选举后要读的10本挑衅性政治小说

...,不知何故渴望更多的选举阴谋,《信息民主》应该是你阅读清单上的下一本书。如果这一切听起来太沉闷,太接近家,太真实,我还有一个建议:贝基商会的漫长的道路,一个小愤怒的星球。尽管书名如此,这本书读起来还是...

- 发布于 2021-05-08 15:16

- 阅读 ( 197 )

尼尔·盖曼的下一部小说是一部名为《七姐妹》的无涯续集

尼尔·盖曼(neilgaiman)刚刚发表了他关于挪威神话(Norse myths)的文章,这位广受欢迎的幻想作家本周早些时候在伦敦的一次活动中提到,他已经开始写下一部小说。《无涯游记》的后续作品将被命名为《七姐妹》。 ...

- 发布于 2021-05-09 23:21

- 阅读 ( 164 )

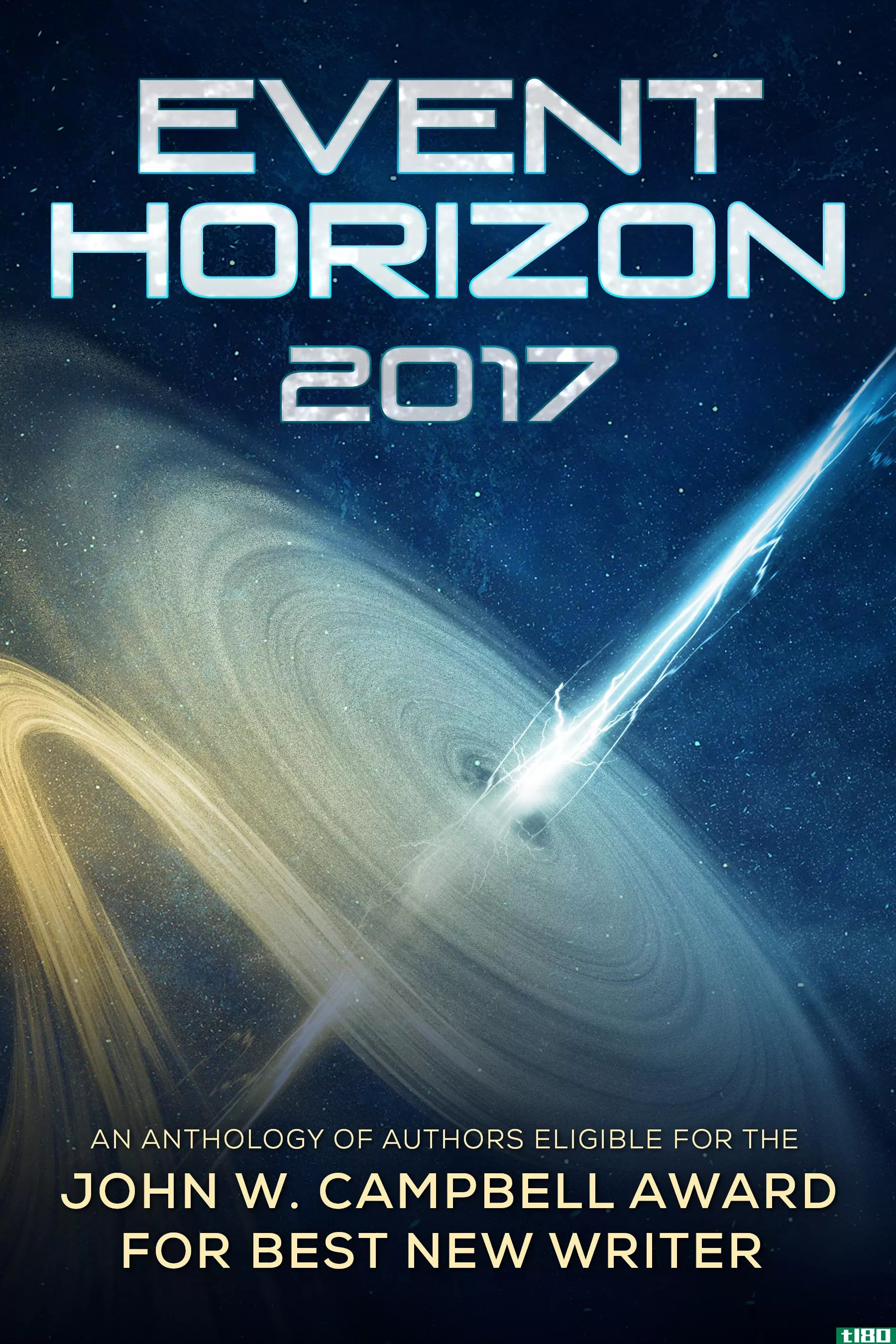

一本新的科幻小说选集收集了后起之秀作家的故事

...的事业,如奥森·斯科特·卡德、约翰·斯卡齐或内奥米·诺维克,但在他们的事业刚刚起步之际发现新人可能是一项挑战,因此一位作家将今年合格作家的故事收集到一本1200页的文集中。 《2017事件地平线》选集由两...

- 发布于 2021-05-10 11:17

- 阅读 ( 141 )