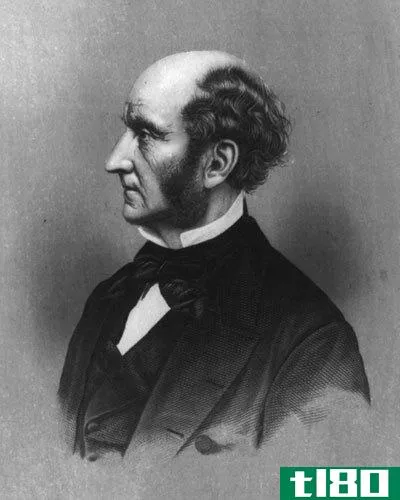

关于约翰·斯图尔特·密尔,一位男性女权主义者和哲学家

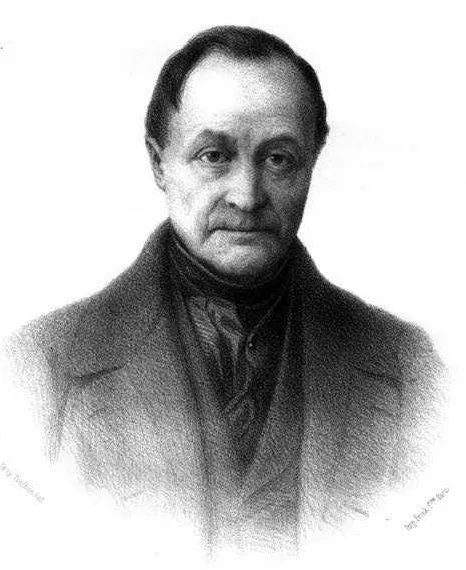

约翰·斯图亚特·密尔(1806-1873)以其关于自由、伦理、人权和经济学的著作而闻名。功利主义伦理学家杰里米·边沁(Jeremy Bentham)在他年轻时就对他产生了影响。米尔,一位无神论者,是伯特兰·罗素的教父。一位朋友是理查德·潘克赫斯特,选举权活动家埃梅琳·潘克赫斯特的丈夫。

约翰·斯图尔特·米尔和哈丽特·泰勒有21年的未婚亲密友谊。她丈夫死后,他们于1851年结婚。同年,她发表了一篇文章《妇女的选举权》,主张妇女能够投票。就在三年前,美国妇女在纽约塞内卡福尔斯举行的妇女权利大会上呼吁妇女享有选举权。米尔斯夫妇声称,露西·斯通1850年女权大会的演讲稿是他们的灵感来源。

哈里特·泰勒·米尔于1858年去世。哈丽特的女儿在随后的几年里担任他的助手。约翰·斯图亚特·米尔在哈丽特去世前不久发表了《自由》杂志,许多人认为哈丽特对这部作品的影响不只是一点点。

“妇女的臣服”

密尔在1861年写了《妇女的臣服》,但直到1869年才出版。在这篇文章中,他主张对妇女进行教育,并为她们争取“完全平等”。他认为哈里特·泰勒·米尔是这篇文章的合著者,但当时或后来很少有人认真对待这篇文章。即使在今天,许多女权主义者也接受了他的话,而许多非女权主义者的历史学家和作家则不接受。这篇文章的开头一段表明了他的立场:

The object of this Essay is to explain as clearly as I am able grounds of an opinion which I have held from the very earliest period when I had formed any opinions at all on social political matters, and which, instead of being weakened or modified, has been constantly growing stronger by the progress reflection and the experience of life. That the principle which regulates the existing social relations between the two sexes - the legal subordination of one sex to the other - is wrong itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality, admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other.议会

从1865年到1868年,米尔担任国会议员。1866年,他提出了一项由他的朋友理查德·潘克赫斯特(Richard Pankhurst)起草的法案,成为有史以来第一位呼吁给予妇女投票权的共和党人。米尔继续倡导妇女投票以及其他改革,包括扩大选举权。他曾担任1867年成立的妇女选举权协会主席。

扩大妇女选举权

1861年,密尔发表了《关于代议政制的考虑》,主张普选,但逐步实行。这是他在议会中许多努力的基础。以下是第八章“扩大选举权”的摘录,其中他讨论了妇女的投票权:

In the preceding argument for universal but graduated suffrage, I have taken no account of difference of sex. I consider it to be as entirely irrelevant to political rights as difference in height or in the color of the hair. All human beings have the same interest in good government; the welfare of all is alike affected by it, and they have equal need of a voice in it to secure their share of its benefits. If there be any difference, women require it more than men, since, being physically weaker, they are more dependent on law and society for protection. Mankind have long since abandoned the only premises which will support the conclusion that women ought not to have votes. No one now holds that women should be in personal servitude; that they should have no thought, wish, or occupation but to be the domestic drudges of husbands, fathers, or brothers. It is allowed to unmarried, and wants but little of being conceded to married women to hold property, and have pecuniary and business interests in the same manner as men. It is considered suitable and proper that women should think, and write, and be teachers. As soon as these things are admitted, the political disqualification has no principle to rest on. The whole mode of thought of the modern world is, with increasing emphasis, pronouncing against the claim of society to decide for individuals what they are and are not fit for, and what they shall and shall not be allowed to attempt. If the principles of modern politics and political economy are good for any thing, it is for proving that these points can only be rightly judged of by the individuals themselves; and that, under complete freedom of choice, wherever there are real diversities of aptitude, the greater number will apply themselves to the things for which they are on the average fittest, and the exceptional course will only be taken by the exceptions. Either the whole tendency of modern social improvements has been wrong, or it ought to be carried out to the total abolition of all exclusions and disabilities which close any honest employment to a human being. But it is not even necessary to maintain so much in order to prove that women should have the suffrage. Were it as right as it is wrong that they should be a subordinate class, confined to domestic occupations and subject to domestic authority, they would not the less require the protection of the suffrage to secure them from the abuse of that authority. Men, as well as women, do not need political rights in order that they may govern, but in order that they may not be misgoverned. The majority of the male sex are, and will be all their lives, nothing else than laborers in corn-fields or manufactories; but this does not render the suffrage less desirable for them, nor their claim to it less irresistible, when not likely to make a bad use of it. Nobody pretends to think that woman would make a bad use of the suffrage. The worst that is said is that they would vote as mere dependents, the bidding of their male relations. If it be so, so let it be. If they think for themselves, great good will be done; and if they do not, no harm. It is a benefit to human beings to take off their fetters, even if they do not desire to walk. It would already be a great improvement in the moral position of women to be no longer declared by law incapable of an opinion, and not entitled to a preference, respecting the most important concerns of humanity. There would be some benefit to them individually in having something to bestow which their male relatives can not exact, and are yet desirous to have. It would also be no small matter that the husband would necessarily discuss the matter with his wife, and that the vote would not be his exclusive affair, but a joint concern. People do not sufficiently consider how markedly the fact that she is able to have some action on the outward world independently of him, raises her dignity and value in a vulgar man's eyes, and makes her the object of a respect which no personal qualities would ever obtain for one whose social existence he can entirely appropriate. The vote itself, too, would be improved in quality. The man would often be obliged to find honest reasons for his vote, such as might induce a more upright and impartial character to serve with him under the same banner. The wife's influence would often keep him true to his own sincere opinion. Often, indeed, it would be used, not on the side of public principle, but of the personal interest or worldly vanity of the family. But, wherever this would be the tendency of the wife's influence, it is exerted to the full already in that bad direction, and with the more certainty, since under the present law and custom she is generally too utter a stranger to politics in any sense in which they involve principle to be able to realize to herself that there is a point of honor in them; and most people have as little sympathy in the point of honor of others, when their own is not placed in the same thing, as they have in the religious feelings of those whose religion differs from theirs. Give the woman a vote, and she comes under the operation of the political point of honor. She learns to look on politics as a thing on which she is allowed to have an opinion, and in which, if one has an opinion, it ought to be acted upon; she acquires a sense of personal accountability in the matter, and will no longer feel, as she does at present, that whatever amount of bad influence she may exercise, if the man can but be persuaded, all is right, and his responsibility covers all. It is only by being herself encouraged to form an opinion, and obtain an intelligent comprehension of the reasons which ought to prevail with the conscience against the temptations of personal or family interest, that she can ever cease to act as a disturbing force on the political conscience of the man. Her indirect agency can only be prevented from being politically mischievous by being exchanged for direct. I have supposed the right of suffrage to depend, as in a good state of things it would, on personal conditions. Where it depends, as in this and most other countries, on conditions of property, the contradiction is even more flagrant. There something more than ordinarily irrational in the fact that when a woman can give all the guarantees required from a male elector, independent circumstances, the position of a householder and head of a family, payment of taxes, or whatever may be the conditions imposed, the very principle and system of a representation based on property is set aside, and an exceptionally personal disqualification is created for the mere purpose of excluding her. When it is added that in the country where this is done a woman now reigns, and that the most glorious ruler whom that country ever had was a woman, the picture of unreason and scarcely disguised injustice is complete. Let us hope that as the work proceeds of pulling down, one after another, the remains of the mouldering fabric of monopoly and tyranny, this one will not be the last to disappear; that the opinion of Bentham, of Mr. Samuel Bailey, of Mr. Hare, and many other of the most powerful political thinkers of this age and country (not to speak of others), will make its way to all minds not rendered obdurate by selfishness or inveterate prejudice; and that, before the lapse another generation, the accident of sex, no more than the accident of skin, will be deemed a sufficient justification for depriving its possessor of the equal protection and just privileges of a citizen. (Chapter VIII "Of the Extension of the Suffrage" from Considerations of Representative Government, by John Stuart Mill, 1861.)- 发表于 2021-10-15 21:49

- 阅读 ( 225 )

- 分类:人文

你可能感兴趣的文章

实证主义(positivism)和经验主义(empiricism)的区别

...识)。 我们通常把实证主义学说的发展归因于19世纪法国哲学家奥古斯特·孔德。孔德认为,“我们的每一个知识分支都先后经过三个不同的理论条件:神学的,或虚构的;形而上学的,或抽象的;科学的,或积极的。”最后一...

- 发布于 2020-10-21 16:06

- 阅读 ( 2037 )

功利主义(utilitarianism)和道义论(deontology)的区别

...然而,当关注道义论时,它与功利主义是不同的。 约翰·斯图尔特·密尔 什么是道义论(deontology)? 道义论在解释其概念时,与功利主义正好相反。道义论不相信“目的证明手段正当”的概念。另一方面,它说“目的不能证明手...

- 发布于 2020-10-26 10:13

- 阅读 ( 1204 )

功利主义(utilitarianism)和义务学(deontology)的区别

...功利主义和义务论的伦理体系。 功利主义是哲学家约翰·斯图尔特·密尔和杰里米·边沁提出的“目的证明手段正当”的概念。它认为,与后者相比,行动的结果具有更大的价值。它还指出,最合乎道德的做法是利用幸福为社会...

- 发布于 2021-06-23 17:51

- 阅读 ( 729 )

自由主义的(liberal)和进步的(progressive)的区别

...称,是第一位将这些自由主义的平等思想赋予权威的英国哲学家和政治思想家。骆家辉宣扬了一种激进的观点,即**必须征得被统治者的同意才能执政,**在得到同意之前仍然是合法的。17世纪英国的光荣革命,使英国、苏格兰和...

- 发布于 2021-06-24 17:30

- 阅读 ( 367 )

理性主义(rationalism)和经验主义(empiricism)的区别

...都是著名的理性主义者。 经验主义:约翰·洛克、约翰·斯图尔特·密尔和乔治·伯克利是一些著名的经验主义者。 Image Courtesy: “Immanuel Kant (painted portrait)” By Anonymous – (Public Domain) via Comm*** Wikimedia “约翰洛克”由戈弗雷·克内...

- 发布于 2021-06-28 03:05

- 阅读 ( 407 )

朱迪芝加哥的晚宴

...安东尼:19世纪妇女选举权运动的主要发言人。她是那些女权主义者中最熟悉的名字。 33. 伊丽莎白·布莱克威尔当前位置她是第一位从医学院毕业的女性,也是在医学领域教育其他女性的先驱。她开办了一家医院,由她的姐姐...

- 发布于 2021-09-04 03:39

- 阅读 ( 337 )

简要阐述了功利主义的三个基本原则

...要、最有影响的道德理论之一。在许多方面,这是苏格兰哲学家大卫·休谟(1711-1776)及其18世纪中期著作的观点。但在英国哲学家杰里米·边沁(1748-1832)和约翰·斯图亚特·密尔(1806-1873)的著作中,它既得到了它的名字,也...

- 发布于 2021-09-04 16:41

- 阅读 ( 305 )

世界历史上最重要的100位女性

...选举权的组织者,组织了国际选举权领袖 贝蒂·弗里丹:女权主义者,他的书推动了所谓的“第二波” Gloria Steinem:理论家和作家,她的《女士》杂志帮助塑造了“第二波” 国家元首 古代、中世纪、文艺复兴 哈特谢普苏特...

- 发布于 2021-09-04 20:21

- 阅读 ( 314 )

《论美德与幸福》,约翰·斯图尔特·密尔著

英国哲学家和社会改革家约翰·斯图尔特·密尔是19世纪的主要知识分子之一,也是功利主义社会的创始成员。在以下摘录自其长篇哲学论文《功利主义》的部分中,密尔依靠分类和划分策略来捍卫“幸福是人类行为的唯一目的...

- 发布于 2021-09-09 15:25

- 阅读 ( 181 )

里德五世。里德:消除性别歧视

...同待遇”这是违宪的。 致力于平等权利修正案(ERA)的女权主义者指出,法院花了一个多世纪的时间才承认第14条修正案保护了妇女的权利。 第十四修正案 第14条修正案规定了法律下的平等保护,被解释为意味着处于类似...

- 发布于 2021-09-11 22:01

- 阅读 ( 176 )